The widespread celebrations on the 40th anniversary of the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 2008, provide a timely opportunity for reflections on the process through which King has been constructed as a mythical figure in the US, while having been purged of his most radical features at the same time. The process used in fact is not new. With the ultimate undercurrent to blunt the sharpest points of a protest movement, a common pattern has been established: first, eliminating its leader; then, turning him into a martyr; and, finally, transforming him into a myth. This article surveys representations of Martin Luther King, Jr., over the last 40 years and argues that the same pattern was followed in his canonization, closely tied to retrospective reflections on the civil rights movement itself.

The exact circumstances of his death – like those of the killing of John F. Kennedy and of his brother Robert F. (killed two months after King, on June 5, 1968) – are still controversial (the official account of the assassination has been challenged, among others, by Pepper 2008). What is certain is that right after April 4, 1968, when King was assassinated on the balcony of his room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, a process of canonization started to transform him into the martyr-symbol of the war against racism and racial discrimination, constructing a mythical figure, purged of the features more in conflict with the image of the incorruptible American hero.

Left, picture taken on Feb. 22, 1956 at the police station in Montgomery, Alabama; right, icon sold on the internet.

Every process of canonization poses complex problems of interpretation, and in the case of King it is not easy to understand how a black Baptist minister could have become the “Holy Martin” of a Byzantine style icon, with an inscription in Greek, and appear in several other sacred images, like the one in the stained glass window of St. Edmund’s Episcopal Church in Chicago. King’s consecration is confirmed by the inclusion of his name, as “renewer of society, martyr, 1968”, in the Lutheran Book of Worship, which includes the liturgical calendar of the two main Lutheran denominations (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod), and as “Civil Rights Leader” in the Book of Common Prayer of the Episcopal Church (on King’s canonization, see Hoffman 2000).

According to Keith Miller, the language used by King himself has been the main source of inspiration for this process (Miller 1992). In fact, in his speeches King often identified himself with biblical figures and made use of biblical metaphors, leading his audience to consider the civil rights movement as a modern reenactment of the Exodus, and to look upon him as a new Moses. However, King’s actions were as important as his language in transforming him into a national icon and symbol of the civil rights movement. The mass media played a crucial role in making King the leader of the movement, thus overshadowing all other leaders, and obscuring the fact that it was a grass-roots movement supported by the vast majority of the Southern black population. Moreover, the “King-centric” version fails to acknowledge that the movement was only one part of a much broader struggle and a much longer “civil rights era” (see Singh 2004).

If King’s canonization has facilitated the integration of the myth into shared national memory, on the political level the construction of the myth of King as the apostle of nonviolent action against racial discrimination, who suffered martyrdom for his words and activities, has served more than one goal: emphasizing the utopian and nonviolent aspects of his message helped to diminish the importance of aspects which were more openly critical of American society and politics, and at the same time put him in opposition to Malcolm X, assassinated three years before, whose memory could not be adopted to the American dream (on the progressive convergence of perspectives of the two leaders, see Cone 1992). In order to reach these goals, it was necessary to freeze King’s public image at the August 1963 march on Washington, focusing on the speech delivered on that occasion, especially the famous conclusion, which presented his “dream” – to be sure a great example of the homiletic tradition of black preachers. That speech is now universally known and referred to as “I Have a Dream” (Washington ed. 1986, 227-30) and is quoted and eulogized as the apex of the life and message of the Baptist minister. Quite often, in official celebrations of King, nothing is mentioned between that speech and his death, as if in those five years – from August 28, 1963, to April 4, 1968 – nothing noteworthy had happened.

Why was it necessary to identify King’s message with the last part of that speech? Because, while the first part denounced as a nightmare the intolerable condition of millions of black people who lived “on a lonely island of poverty” and were “in exile in [their] own land” (Washington ed. 1986, 217) the last part simply reflected King’s trust in the American dream and praised it notwithstanding its unfulfilled status. In King’s words, inspired by a speech delivered by Archibald Carey at the National Republican Convention of 1952, the appeal to the American dream, unrealized but still possible, resounded high and enticing: Let us not wallow in the valley of despair. So I say to you, my friends, that even though we must face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream” (Washington ed. 1986, 219). It could not be otherwise, because this is the “manifest destiny” of the American nation. One should not forget that the utopian component has been part of the American ideology from the very beginning – from John Winthrop’s famous reminder to his fellow travellers to the Promised Land that their experiment “shall be as a City upon a Hill”, a light and a model for the World, and from Tom Paine’s proclamation, at the outset of the American Revolution: “We have it in our power to begin the world over again” (Paine 1995, 92).

The dream of a new society, offering new possibilities to everyone, has resisted the erosion of history, the extermination of the natives, the slavery of blacks, and the hardships of the Great Depression. But even when the dream has revealed itself to be a nightmare, it has not lost its capacity to stir the hopes of those who want to continue to believe in a nation which could be different from what it is. As the poet Langston Hughes, one of the main representatives of the “Harlem Renaissance”, wished in “Let America Be America Again”, written in 1938:

Let America be America again.

Let it be the dream it used to be.

[…]

Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed.

The titles of the two books written by President Barack Obama, Dreams from My Father (1995) and The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream (2006), offer a good example of the evocative value that the term “dream” still has in American political discourse.

However, that dream is less and less traceable in King’s speeches and writings in the period between the 1963 march on Washington and his death, because his protest was becoming more and more oriented toward a rigorous denunciation of the connections between racism, poverty, and injustice. Therefore, it has been considered necessary to reconstruct his memory on the basis of “I Have a Dream”.

On this premise is founded the conventional image presented at most celebrations of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the federal holiday instituted in 1983 by the United States Congress during Ronald Reagan’s first presidency, in spite of attempts by some conservative representatives and senators to prevent its approval. Jesse Helms, Republican Senator from North Carolina, criticized King’s stand against the Vietnam War and accused him of collusion with communists, as discussed by Dewar (1983). John McCain, Republican candidate for the 2008 presidential elections, also spoke out against the Congress’s decision initially, but subsequently admitted that he had made a mistake. This holiday has been observed from 1986 on the third Monday of January. The first proposal to institute a national holiday commemorating King’s birthday was presented to the House by John Conyers (D., Michigan) only four days after King’s death. Later, on January 15, 1969, the King Center of Atlanta, created by King’s widow, Coretta Scott, promoted the first annual celebration at the local and national levels. However, the bill would most likely have become stranded in a House committee, “had it not been for thousands of working-class Americans – most of them black, but also white, Asian and Latino – who risked their jobs over the next fifteen years to demand the right to honor a man they viewed as a working-class hero” (Jones 2006, 23-4). But this long struggle of many American workers is almost ignored and the credit for the institution of the national holiday is assigned to the campaign launched by the King Center with the support of famous figures like musician Stevie Wonder, who dedicated the song “Happy Birthday” to King in 1980, and of politicians like Rep. Katie B. Hall (D., Indiana, 1982 and 1985) (Baldwin 1992, 286-301).

On December 5, 1955, at the start of the boycott of the Montgomery urban transportation system, in an address given in the Holt Street Baptist Church, King declared that “the great glory of American democracy is the right to protest for right” and this firm belief sustained him throughout his short life.

King’s thought constantly interacted with the social and political problems of his time and his actions and words were deeply affected by this interaction. In other words, King constantly adapted and reworked his message, which combined a substantial continuity based on the search for justice, with a change and enlargement of the original perspective.

If it was right to protest against racial segregation in Montgomery, during the following years King’s nonviolent struggle focused on racism and the non-implementation of the abolition of every form of racial segregation, as called for by the Supreme Court decision on Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas in 1954. This period culminated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, as it was officially called, whose chief organizer was the labor leader A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the largest black union in the country.

Thereafter, King became increasingly concerned with the interrelation between racism, injustice and poverty. In 1964, he participated in the Mississippi Freedom Summer, during which three young black people were killed. In February 1965, he went to Selma, Alabama, where he was arrested and thus could not meet Malcolm X – the former Black Muslim leader who had been critical of the nonviolent method adopted by King but was in the process of revising his position – until he was killed a few days later. From March 21 to 25, King participated in the march from Selma to Montgomery, the city where his nonviolent struggle against racial segregation had begun ten years earlier. There he launched once more his call to fight for the accomplishment of the American dream: “Let us […] continue our triumphant march to the realization of the American dream” (Washington ed. 1986, 227-30).

On August 11, 1965, a few days after the Voting Rights Act was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, racial violence exploded in the Watts area of Los Angeles. By that time King had already decided that he could not avoid confronting the reality of urban ghettos and that he had to take up Malcolm X’s inheritance. For this reason he immediately went to Watts and, a few months later, to Chicago, where another riot had erupted.

Finally, beginning early in 1967, it became time “to break the silence” on the Vietnam War and to expose the militarism that pervaded American society and politics. In his first speech fully devoted to Vietnam (Los Angeles, February 25, 1967), King declared that “the bombs in Vietnam also exploded at home; they destroyed the hopes and possibilities for a decent America” (Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Dr. John C. Bennett, Dr. Henry Steele Commager, Rabbi Abraham Heschel Speak on the War in Vietnam 1967, 5-9).

In his addresses against the war and United States foreign policy, the American dream was no longer mentioned. It had once again been transformed into a nightmare by a war for which “the poor of America […] are paying the double price of smashed hopes at home, and death and corruption in Vietnam” (Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Dr. John C. Bennett, Dr. Henry Steele Commager, Rabbi Abraham Heschel Speak on the War in Vietnam 1967, 10-16). The rhetoric of the dream was replaced by a heartfelt appeal to act for peace and justice. In the villages destroyed by napalm the dream had been shattered once again. But there was “something even more disturbing,” that is, the fact that “the war in Vietnam [was] but a symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit. […] A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death” (ibid.)

King’s address at the Riverside Church of New York on April 4, 1967, in which he most fiercely attacked American foreign policy, was defined by Life magazine as a “demagogic slander that sounded like a script [for] Radio Hanoi” (April 21, 1967 and, according to The Washington Post, “[King] diminished his usefulness to his cause, to his country, to his people” (April 6, 1967) (cf. “Dr. King’s Error,” New York Times, April 7, 1967).

During the last part of his life, King also continued and intensified his struggle for the rights of the working class, which had characterized all of his public life since the bus boycott of Montgomery in 1955. In a speech delivered to the state convention of the Illinois AFL-CIO in 1965, he claimed:

The labor movement was the principal force that transformed misery and despair into hope and progress. Out of its bold struggles, economic and social reform gave birth to unemployment insurance, old age pensions, government relief for the destitute, and above all new wage levels that meant not mere survival, but a tolerable life. The captains of industry did not lead this transformation; they resisted it until they were overcome.

As then Senator Obama also recalled in a speech celebrating the 40th anniversary of King’s death, he was killed while in Memphis assisting striking AFSCME sanitation workers who demanded recognition of their union, because he was convinced that “the struggle for economic justice and the struggle for racial justice were really one – that each was part of a larger struggle for freedom, for dignity, and for humanity.” Obama observed that “the struggle for economic justice remains an unfinished part of the King legacy, because the dream is still out of reach for too many Americans” (Obama 2008).

With this reality staring us in the face, the myth of King continues to be constructed, backed up by his heirs who, also in their own interests, acquired the exclusive right in 1982 to exploit his image for commercial aims, even in military bases both within the United States and in the rest of the world. From 1996 onwards the King Center grants licenses for the sale of his personal effects and the use of his writings. The Lorraine Motel, where King was shot to death, was turned into the National Museum of Civil Rights in 1991; a new section, “Exploring the Legacy”, was opened to the public on September 28, 2002. Statues of King have been erected in various parts of the United States: Raleigh, North Carolina, Stockton, California, Portland, Oregon, and Austin, on the campus of the University of Texas.

Detail of the bronze statue in the King Memorial Gardens, in Raleigh, N.C.

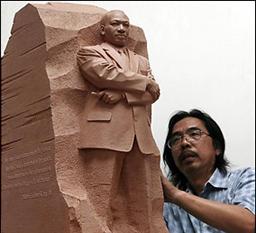

Meanwhile, in Washington, the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial, which lies between the Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials, is well on its way to completion. This mausoleum, whose inauguration is planned for 2009, will mark the ultimate consecration of King as a prophet of the American dream, which consists of “Freedom, Democracy and Opportunity for All” (Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial, Vision Statement). A large statue of King, by the Chinese sculptor Lei Yixin, will stand at the center of the Memorial, which will be a new temple of American civil religion, a new shrine for the pilgrimage made every year by millions of Americans to visit the monuments dedicated to Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln, and the Holy Writings (the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights), on display in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom of the National Archives.

The sculptor Lei Yixin with his terracotta model of the statue of Martin Luther King, which will be placed in the center of the King Memorial in Washington.

The words written by the poet Carl Wendell Hines in 1971 seem prophetic:

Now that he is safely dead,

Let us Praise him.

Now that he is safely dead,

Let us Praise him.

Build monuments to his glory.

Sing Hosannas to his name.

Dead men make such convenient Heroes.

They cannot rise to challenge the images

We would fashion from their Lives.

It is easier to build monuments

Than to make a better world.

So now that he is safely dead,

We, with eased consciences, will

Teach our children that he was a great man,

Knowing that the cause for which he

Lived is still a cause

And the dream for which he died

Is still a dream. (Hines 1987, 468).

For many Americans the dream has remained just that, a dream. Will President Obama be able to restore it? Could the dream of equality for all American citizens finally be realized?

Works Cited

- Baldwin, Lewis V. To Make the Wounded Whole: The Cultural Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1992.

- Cone, James H. Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1992.

- Dewar, Helen. “Helms Stalls King’s Day in Senate.” Washington Post (Oct. 4, 1983): A1.

- “Dr. King’s Error,” New York Times (April 7, 1967)

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Dr. John C. Bennett, Dr. Henry Steele Commager, Rabbi Abraham Heschel Speak on the War in Vietnam. [New York]: Committee of Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam. 1967.

- Hines, Carl Wendell. “Now That He Is Safely Dead.” Cit. in Vincent G. Harding, “Beyond Amnesia: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Future of America,” Journal of American History, 74 (September 1987): 468.

- Hoffman, Scott W. “Holy Martin: The Overlooked Canonization of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.,” Religion and American Culture 10 (Summer 2000): 123-148.

- Jones, William P. “Working-Class Hero: The Forgotten Labor Roots of the Martin Luther King Holiday,” The Nation (Jan. 30, 2006): 23-4.

- King, Martin L. “I Have a Dream.” A Testament of Hope. The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr. James M. Washington (ed.). New York: HarperCollins, 1986. 217-20.

- King, Martin L. “Our God is Marching On!” A Testament of Hope. The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr. James M. Washington (ed.). New York: HarperCollins, 1986. 227-30.

- King, Martin L. “Speech to the State Convention of the Illinois AFL-CIO” Oct. 7, 1965. Life (April 21, 1967): 4

- Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial, Vision Statement. Access: April 10, 2008. http://www.mlkmemorial.org/site/c.hkIUL9MVJxE/b.1232927/k.9567/Mission__Vision.htm

- MIA Mass Meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church. Access: April 10, 2008. http://stanford.edu/group/King/publications/papers/vol3/551205.004-MIA_Mass_Meeting_at_Holt_Street_Baptist_Church.htm.

- Miller, Keith D. The Voice of Deliverance: The Language of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Its Source. New York: Maxwell Macmillan, 1992.

- Obama, Barack. “Remarks by Senator Barack Obama on Martin Luther King Jr.” The Boston Globe (April 4, 2008). Access: April 10, 2008.

http://www.boston.com/news/nation/articles/2008/04/04/remarks_by_senator_obama - Paine, Thomas. Collected Writings. New York: The Library of America, 1995.

- Pepper, William. An Act of State: The Execution of Martin Luther King, 2nd ed. London & New York: Verso, 2008.

- Singh, Nikhil Pal. Black Is a Country: Race and the Unfinished Struggle for Democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- “A Tragedy.” Washington Post (April 6, 1967).

Copyright (c) 2009 Massimo Rubboli

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.